Warp Gates in Science Fiction: Video Games and Space-Opera Portrayals

Devlog: Wormhole Gateways

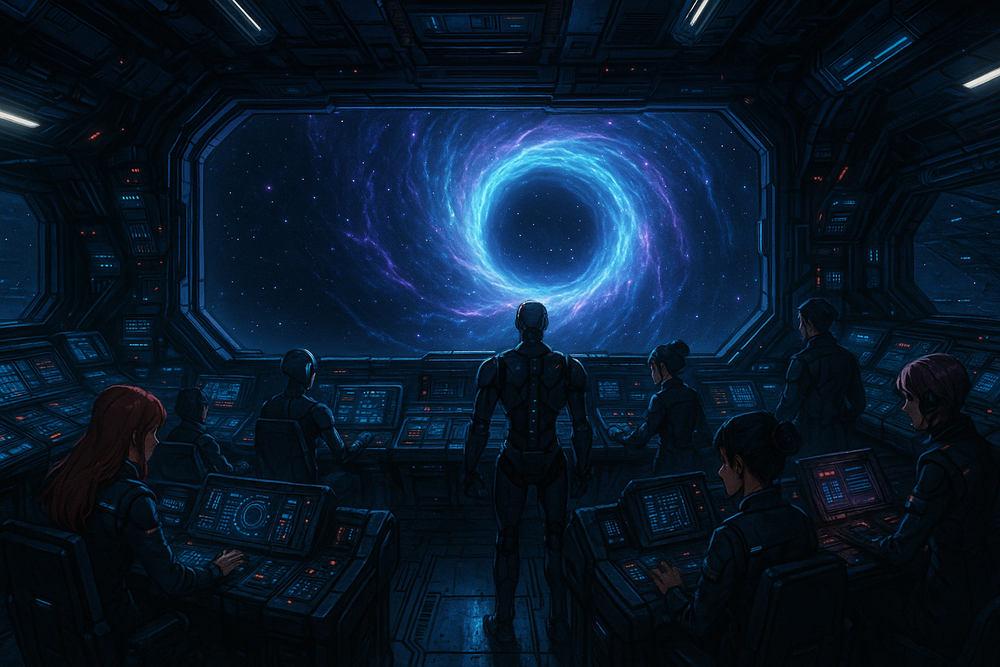

We’ve just implemented the wormhole gateways in Wardrome — and they’re finally operational. For now, the mechanic is simple: the player’s fleet approaches a gate, it powers up, and the ships are transferred to an adjacent sector.

In the future, however, these wormhole tunnels will become far more than just shortcuts. We’re planning to add adventures and encounters within the hyperspace corridor itself — mysterious, unpredictable, and full of secrets.

The sequence also features a brand-new track from the Wardrome Original Soundtrack, titled “Wardrome Through the Wormhole”, which will be released soon on all streaming platforms.

You can see the current implementation in action in this short devlog video:

Before deciding how our gateways should function, we explored how warp gates and wormholes have been represented across sci-fi games and media. That research follows below.

Engage!

Warp gates (also known as stargates, jump gates, or wormholes) are a staple of science fiction, providing near-instantaneous travel between distant points in space. They appear across video games, novels, TV series, and films, serving both gameplay needs and narrative drama. This report examines how warp gates are implemented in sci-fi video games – covering gameplay mechanics, player interaction, limitations, and map design – and how similar constructs are depicted in space-opera literature and on screen. We highlight specific examples by franchise and identify recurring design patterns that could inform development in Wardrome.

Warp Gates in Sci-Fi Video Games

Gameplay Mechanics and Map Design

In many sci-fi games, fixed gate networks strongly shape how players navigate the world. Warp gates often function as fast-travel nodes that connect star systems or regions, effectively defining the game’s map topology. Key examples include:

- EVE Online: Stargates link adjacent star systems and form the backbone of New Eden’s travel routes (eve.fandom.com). Players must pilot within 2,500 meters of a gate to initiate an instant jump to the next system (wiki.eveuniversity.org). After a jump, ships arrive near the destination gate (about 12 km away) under a brief cloak. Game mechanics make gates strategic chokepoints: combat is common at gate entrances, but rules prevent immediate pursuit if a player has fired weapons (an aggression timer imposes a 60-second delay before they can follow through a gate).

Certain large capital ships cannot use stargates at all and instead rely on other FTL methods, ensuring that gates primarily serve sub-capital traffic.

This design creates natural trade routes and ambush spots (so-called “gate camps”) which add risk and strategic value to controlling gate areas. - X Series (Egosoft’s X: Beyond the Frontier and sequels): The game universe consists of dozens of sectors connected by jump gates arranged in a fixed grid (usually with gates at the north, south, east, west edges of each sector) x-universe.fandom.com. These ancient gates, built by an unknown precursor, form a semi-permanent network through which all travel occurs.

Early on, players can only reach nearby sectors via the available gates, meaning exploration and expansion are gated by discovering new gate connections. The gate network defines clear frontiers and choke points, which the player can exploit for trade or military blockades. Notably, in the X lore, a catastrophic shutdown of the gate network at one point isolates systems – a dramatic map-changing event that later games (e.g. X4: Foundations) build stories around. This illustrates how controlling gate availability can drive gameplay progression and map design in a sandbox universe. - Freelancer: In this space sim, humanity’s colonies are spread across the Sirius Sector, connected by two types of FTL routes: Jump Gates and Jump Holes. Jump Gates are large, man-made rings (developed by the in-game corporation Ageira Technologies) that provide safe, instantaneous travel between specific systems (freelancer.fandom.com). These gates are expensive infrastructure, typically built along heavily-trafficked trade corridors. By contrast, Jump Holes are naturally-occurring wormholes – unstable and uncharted – that link systems in a more haphazard way. For gameplay, the gated network means players follow defined paths (often patrolled by authorities), whereas jump holes offer risky shortcuts useful for pirates or during certain missions. The map is essentially a graph of gate connections, and some areas remain off-limits until story events unlock their jump gates. This design balances open exploration with structured progression: the player can free-fly within a star system, but to reach a new star system they must find a working gate or hole.

- Mass Effect series: While the player’s ship has a conventional FTL drive for local travel, long-distance interstellar travel relies on the network of Mass Relays. These enormous twin-armed constructs are ancient devices that fling ships through a mass-free corridor of space-time, connecting relay to relay in seconds (masseffect.fandom.com). In gameplay terms, the galaxy map is segmented by relay links – each relay connects to one or a few others (some are paired one-to-one). The player selects a destination relay and “jumps” there via a cutscene. This effectively loads a new cluster of star systems to explore. Map design-wise, Mass Relays create clusters of content: the player cannot visit another galactic sector without going through the appropriate relay. This structure gates progress to certain story-critical regions until the narrative permits access. It also introduces resource management in later games (Mass Effect 2 requires ship fuel for inter-relay travel, and running out leaves the ship stranded until you send a distress call). Though the relay jumps themselves are not interactive (they occur in cutscenes), the reliance on fixed relay nodes is a clear design choice to compartmentalize the vast galaxy into manageable chunks for the player.

- 4X and Strategy Games: Grand strategy titles often incorporate gate or lane mechanics to shape strategic movement. In Stellaris, for example, the early game uses natural hyperlanes between star systems (no free-form jumping), and later players can research Gateway technology – reactivating ancient gateways or building new ones. Once active, a Gateway allows instantaneous transit to any other active gateway, effectively creating a fast-travel network across the galaxy (stellarisinvicta.fandom.com). This dramatically alters map strategy: empires can reinforce distant fronts in a flash or launch deep strikes via gateways. Controlling a gateway can become as vital as holding a planet. The game even allows “closed borders” diplomacy to restrict enemy use of your gates. Similarly, Sins of a Solar Empire uses fixed phase lanes between planets (analogous to jump gates) to define warpaths, and destroying or fortifying key lane junctions is a major tactical element. These examples show how map topology defined by warp links can be a core layer of strategy gameplay.

- Roguelike and Mission-Based Games: Some titles present warp gates as level transitions. In Everspace, each sector ends with a Jump Gate that the player must reach to progress to the next area. These gates were established by colonists and require no fuel to use, serving as checkpoints between the game’s procedurally generated sectors (everspace.fandom.com). While combat can occur around them, the gates themselves function as safe portals once the player activates them. In mission-based games like Wing Commander or FreeSpace, jump points (or jump nodes) in space are the “exit doors” from a mission zone – often the goal of a mission is simply to survive and get to the jump node to retreat. In these cases, warp points provide pacing: they cleanly mark the end of an encounter and the start of the next scenario.

Gameplay Pattern – Rules & Limitations: Across games, developers impose rules on gate use to balance gameplay. Common patterns include: only small/medium ships can use gates (EVE’s ban on capitals in stargates), requiring specific items or quests to unlock a gate (e.g. finding activation codes or power cells in RPGs), cooldowns or charges for gate jumps, and potential dangers like arrival ambushes or transit damage. For instance, Mass Effect lore notes that ships emerge from a relay with unpredictable “drift” of thousands of kilometers, preventing precise ambushes. Meanwhile, Babylon 5: I've Found Her (a space sim) incorporates the show’s rule that opening a jump point (into hyperspace) requires significant energy, so only capital ships or stationary gates can do it – fighter craft must piggyback on an existing gate. All such rules ensure that warp gates enhance gameplay rather than trivialize it, by adding costs, prerequisites, or risks to instant travel.

Narrative Integration and Visual Design in Games

Beyond mechanics, sci-fi games also use warp gates to enrich world-building, plot, and visual spectacle. Many games borrow from or contribute to the lore of warp gates established in other media. Some noteworthy portrayals include:

- EVE Online – Living Universe Lore: In EVE’s backstory, stargates are a mix of human and alien engineering. The fallen Terran civilization had seeded the galaxy with gate technology; the present-day empires learned to construct their own gates, but these require linked pairs and enormous energy. Each of the four major factions in EVE has its own gate architecture aesthetic (Amarr gates are golden and ornate, Caldari gates are utilitarian and angular, etc.). These designs not only differentiate the look of regions visually, but also imply the political ownership of territory at a glance. Some special gates have story significance – for example, the Old Man Star gate built into an asteroid has a unique backstory in lore (wiki.eveuniversity.org). The presence of sentry guns at high-security gates (NPC defenses) is explained diegetically as well: the empires protect their gateways from pirates. EVE’s chronicle also includes closed or missing gates that strand systems (echoing a post-apocalyptic trope). All these elements tie the gameplay function of stargates into the narrative fabric of the world, making them feel like natural parts of society (with commerce, piracy, and military strategy all revolving around gate access).

- Mass Effect – Ancient Relics Driving the Story: The Mass Relays in Mass Effect are central to the series’ lore and cinematic identity. Visually, a mass relay is a colossal two-pronged structure with rotating element-zero rings and a glowing core – an image instantly recognizable to fans. The lore twist is that these relays (and the Citadel hub) were not built by the benevolent precursor race (the Protheans) as everyone believes, but by the Reapers – a cyclically returning nemesis. Thus the gate network is actually a trap, guiding younger civilizations along pre-set paths. This revelation in the story re-frames the common sci-fi trope: the convenient galaxy-wide network has an ominous purpose. Narrative moments directly involve relays, such as a major decision in Mass Effect 2 where the player’s team destroys a relay to stop an invasion, at the cost of an entire star system – an act presented as gravely consequential due to the enormous energy release (in lore, a mass relay explosion is basically a supernova). In Mass Effect 3, the relays are targeted to cut off the Reapers’ travel or, in the ending, all relays are potentially destroyed to halt the cycle. Thus, warp gates here are not just background infrastructure but plot catalysts. The visual sequences of using a relay – the Normandy spacecraft aligning and then being hurled forward in a flash – are cinematic high points underlining that a significant journey is occurring. The game codex even discusses how relays function scientifically (reducing mass to zero and opening a tunnel) and notes the tactical limitation that ships exit with some random offset distance. By blending the gameplay mechanic with deep lore and impressive visuals, Mass Effect turns warp gates into a thematic symbol of the galaxy’s interconnected fate.

- Freelancer – World-Building through Gates: Freelancer’s narrative is subtly conveyed through its gates and lanes. Each major colony (Liberty, Bretonia, Kusari, Rheinland) operates gate technology based on an alien artifact discovery, and the monopoly on this tech by the Ageira corporation is “Liberty’s most valuable secret”. The existence of hidden jump holes is often used in story missions to facilitate clandestine movement or surprise attacks. For example, the game’s early plot has the player fleeing via a smuggler’s jump hole when official gates are shut down during a crisis. Visually, the jump gates have a blue-white swirling vortex when activated, very much evoking the classic idea of a portal. In contrast, jump holes appear as unstable, wavy gravitational anomalies in space. NPC dialogue and infocards in bars will mention gate construction or recent gate failures, painting a picture of a frontier society where control of warp routes equals economic power. The aesthetic of traveling through a gate is a scripted tunnel-flight sequence – a common visual shorthand for FTL transit that many games use (also seen in FreeSpace and Wing Commander). It’s a brief “wormhole ride” that masks loading the next sector but adds to the immersive feel of being shot through space. Overall, Freelancer integrates its gate mechanics into the lore by showing the contrast between sanctioned, high-tech gateways and dangerous natural shortcuts, reflecting a theme of order versus chaos in its world.

- No Man’s Sky – Portals as Ancient Mysteries: In the exploratory sandbox No Man’s Sky, players can discover and activate planetary portals. These are monolithic ring structures on planets’ surfaces, covered in glyph markings, clearly inspired by the Stargate franchise in appearance (nomanssky.fandom.com). When activated (using a sequence of alien glyphs that function like an address), a portal will create a shimmering vertical plane and allow the player to step through, emerging on another world light-years away. From a gameplay perspective, this provides a way to fast-travel or visit specific coordinates (often shared by the community) without using one’s starship. Narratively, the portals are tied into the game’s enigmatic lore about ancient civilizations (the Travellers, Atlas, etc.). The process to activate one involves seeking monoliths and unlocking glyphs through interactions with alien Travelers. The first time a portal is activated in the story, it’s treated with a sense of wonder and slight dread – much like a sci-fi show where the characters stumble on an alien gate for the first time. The visual effect is striking: a vertical ripple in space that the player walks through, instantly finding the sky and environment changed on the other side. There’s even a nod to Stargate’s dial-up mechanic: the portal has a circular interface with glyphs that rotate and lock (akin to chevrons) when the address is input. By making the portals a diegetic part of the universe (ancient teleporters left by unknown beings) and a quest-driven feature, No Man’s Sky merges the game utility of warp gates with a sense of discovery and homage to classic sci-fi gate lore.

- Homeworld Series – The Great Network: While the Homeworld RTS games mostly depict FTL travel as ships using their own hyperdrives between mission levels, the lore in Homeworld 2 introduces the discovery of an intergalactic hyperspace gate network. The protagonists learn that an ancient race (the Progenitors) built a system of gigantic gates eons ago; unlocking the gate called the Eye of Aarran suddenly allows the Hiigaran people to reach distant galaxies (homeworld.fandom.com). In the game’s final mission, the player actually activates the Eye of Aarran using the protagonist ship Sajuuk, opening a colossal gateway. The cutscene and narration convey this as a watershed moment (“What lay beyond hushed every voice in the Galaxy”). In extended lore (and unofficial expansions), it’s said that the Hiigarans begin exploring and mapping this gate network, but tightly control access to it – causing political tension with other factions who want a share of the new frontier. Here the warp gate concept serves a world-building role: it provides a tantalizing glimpse of a larger universe and sets up plot hooks beyond the scope of the original game. Visually, the hyperspace gates in Homeworld are depicted as massive ring-like structures (one called Balcora Gate is shown in HW2) which generate a luminous tunnel when activated. The grandeur of these gates in the cutscenes reinforces the idea that even a spacefaring civilization regards them as almost divine artifacts. This resonates with a recurring theme in sci-fi: the sudden expansion of horizons (a literal gateway to the stars opening) transforming a civilization. For game developers, it’s an interesting case where a warp gate is not initially part of gameplay, but is introduced in the narrative climax to broaden the lore and possibly to tee up future gameplay possibilities (e.g. a sequel could allow travel between galaxies via these gates).

- Halo Series – Slipspace Portals: Although Halo’s core gameplay revolves around FPS combat rather than piloting ships, the franchise does include portal technology in its story. In Halo 3, the Covenant uncover a gargantuan Forerunner portal structure buried on Earth (the “Portal at Voi” in Kenya) (halopedia.org). When activated by a specific “keyship,” this portal opens a slipspace wormhole to the distant Forerunner Ark installation outside the Milky Way. The game portrays this spectacularly: massive metallic petals rise from the ground and a huge energy sphere forms between them, through which Master Chief and the allied fleet travel. The portal remains open as a staging point, and later in the story it’s a plot point to close or protect it. What’s interesting in Halo’s depiction is the combination of ancient super-technology with military stakes – the portal is essentially a strategic asset that both humans and Covenant covet (it enables rapid reinforcement to the Ark). Visually, it’s depicted as a mix of monolithic structure and roaring sky-born wormhole (the activation causes a swirling storm in the clouds).

Halo’s extended fiction reveals there are other such portal complexes on human colonies, hinting at a whole network left by the Forerunners. This ties into Halo’s broader motif of ancient relics affecting modern warfare. For a game developer, Halo’s portals show how a warp gate can be used sparingly but impactfully – as a set-piece that moves the story to an exotic locale, and as a MacGuffin that multiple factions fight over. It’s less about player travel convenience (since it’s all narrative) and more about driving epic story moments.

Video games have portrayed warp gates in multifaceted ways: as core travel mechanics that define the playable map, as narrative centerpieces rich with lore, and as visual spectacles that awe the player. From the player’s perspective, gates might be everyday infrastructure (as in EVE or X), or mysterious legendary devices (Homeworld, Halo), or even a little of both (Mass Effect’s relays are simultaneously common travel tools and ancient wonders). This duality is often leveraged in game design – the familiarity of using gates regularly can make the story moments where something goes wrong with them (a sabotage, a collapse, an unexpected new gate) all the more powerful.

Warp Gates and Portals in Space-Opera Novels

Science fiction literature is replete with equivalents of warp gates, often serving as crucial world-building elements that enable interstellar societies. Because novels are free from the real-time constraints of gameplay, authors frequently explore the functional implications and dramatic possibilities of such technologies in great detail. Below are several notable treatments:

- “Hyperion Cantos” by Dan Simmons: This epic space-opera features a technology called farcasters, which are essentially teleportation portals connecting vast distances. In the era of the Hegemony of Man, hundreds of planets are linked by farcaster portals into a unified “WorldWeb” (hyperioncantos.fandom.com). People routinely commute between planets via doorways in their homes – Simmons imagines wealthier individuals owning mansions where each room is on a different planet, connected by private farcaster doorframes. The farcasters are so convenient and ubiquitous that the economy and society rely entirely on them. This sets the stage for high drama: at the climax of the second book, all farcaster portals are deliberately destroyed in one moment (to thwart a conspiracy by AIs).

The result is catastrophic collapse – billions of citizens are stranded off-world, colonies are cut off, and the Hegemony falls overnight. Simmons uses the warp-gate network as both a shining achievement and a single point of failure. The recurring design pattern here is an advanced gate system gifted by a shifty benefactor (in this case, the TechnoCore AI) and later revealed to have hidden costs. Indeed, a later twist explains that the farcasters were secretly acting as one giant system rather than many – every time someone teleported, their consciousness spent an eternity in a timeless “white space” used by the AIs for computation. This mind-bending concept turns a normally benign technology into something almost sinister. The Hyperion Cantos thus illustrates the worldbuilding depth possible with portal networks: the author examines how such easy travel changes culture (e.g. people literally have houses spread across planets, and entire planets specialize since goods and people flow freely), and then pulls the rug out to show the chaos of its loss. - Peter F. Hamilton’s Commonwealth Saga (“Pandora’s Star” / “Judas Unchained”): In this universe, humanity develops wormhole generators in the 23rd century, leading to the creation of an interstellar Commonwealth of planets. Rather than starships being the main mode of travel, Hamilton imagines giant trains that run through wormhole tunnels linking planets (peterfhamilton.fandom.com). Each colony world has a terminal where a wormhole exit is projected, often with pressure seals so that atmosphere and even trains can pass through safely. The result is an interstellar railway network – one can literally take a train from London to a city on another planet. The novels describe people seeing the “sky” change as they ride a train through a wormhole, or stepping through a door to instantly arrive light-years away. The wormholes become everyday infrastructure (maintained by a company, CST, which profits immensely from it), to the point that many citizens rarely think about space travel at all. This mundane integration of warp gates is contrasted with the extraordinary: when an alien threat is discovered, one of the responses considered is to sever the wormhole links to isolate the invasion. Additionally, exploring beyond the known network requires sending wormholes out via starships (the exploratory ship Second Chance uses a continuous wormhole drive to deploy new endpoints). Hamilton’s approach underscores a recurring theme in sci-fi literature: gates as the glue of civilization. They can unite worlds into one socio-economic unit (here, a single state spanning worlds), and conversely, the removal or control of gates can become a tool of warfare or rebellion. Visually one can imagine these wormholes as invisible tunnels; the books describe them using terms like “pressure curtain” separating atmospheres. This very concrete detail (needing decompression when you step off a wormhole train) lends realism to the concept. As a development insight, the Commonwealth saga shows an example of warp gates used to eliminate the idea of distance in society – an inspiration for designing game worlds or stories where distance is not a limiting factor until something goes wrong.

- The Expanse series by James S.A. Corey: This modern space-opera starts in a near-future solar system with no FTL, but introduces a game-changing portal mid-series. An alien substance (the protomolecule) constructs a large Ring Gate near Uranus, which turns out to be an entrance to a hub in another dimension (the “slow zone”) leading to a network of 1300+ habitable systems (tvtropes.org). In Abaddon’s Gate and subsequent novels, humanity grapples with the sudden existence of this Stargate-like network. The Ring’s activation shifts the scope of the series from interplanetary to interstellar. Crucially, the authors explore the social and political upheaval: there’s a gold rush of colony ships heading through the gates, Earth and Mars fight over controlling the Ring, and a militant Belter faction tries to destroy or blockade the Ring to maintain the balance of power. The gates themselves have unique rules: anything passing through the Ring space must obey a speed limit (high-speed objects are instantly halted by alien force – as one daring racer finds out fatally). There’s also an enigmatic intelligence left by the gate-builders which reacts lethally when too much energy or aggression happens in the slow zone, leading to ships mysteriously “going Dutchman” (vanishing) if they trigger the wrong response. The Expanse’s treatment is notable for its realism and tension. The Ring isn’t just a magic doorway; it’s an artifact with constraints that become key plot points (e.g. a major character sacrifices himself to shut down the ring network when it threatens to eradicate humanity). This series highlights warp gates as disruptive technology: it asks, what happens if one day a gate appears and renders all our previous transport methods obsolete? Who gets to control it, and what if it leads to unknown dangers? For Wardrome or any game narrative, The Expanse’s scenario is a rich study in turning a gate into a source of conflict and drama, not just a backdrop. It’s essentially a Stargate meets geopolitics approach, with the visual of a lonely Ring floating in space that becomes the most contested location in the solar system.

- “Saga of Seven Suns” by Kevin J. Anderson: In this expansive series, an ancient insectoid race (the Klikiss) had left behind transportals – instantaneous gateways between planets. Various factions vie to control or rediscover these portals. When humans first experiment with a dormant Klikiss transportal, they unwittingly trigger a war with a gaseous alien species, showcasing the classic “gate as Pandora’s box” trope. The transportals allow quick movement of fleets later in the story, but also enable surprise attacks by enemies. As the saga progresses, the hidden network of transportals is gradually mapped, and it’s revealed that some alien factions (the enigmatic wentals and hydrogues) had their own uses for these gates. Anderson’s work reinforces a pattern: ancient gate networks lying dormant until “awakened” by humans are a common catalyst in space-opera. They often bring peril as well as advantage. The existence of a transportal network also forces characters to think in new strategic terms – front lines and alliances shift because distance is no longer a barrier. While not as widely known as some other series, Saga of Seven Suns contributes to the recurring idea of gates being leftover technology from a bygone era that new civilizations co-opt (or fight over) with mixed results.

- Classic and Other Examples: Many other novels feature similar constructs:

- “The Forever War” (Joe Haldeman) – Humans deploy soldiers via collapsars, which are essentially one-way wormhole endpoints near black holes. Troops instantly jump through collapsars to reach distant fronts. This allows the story to explore relativity (subjective time vs. objective time) in a war context, as the portal jumps combined with time dilation mean soldiers return home to a vastly changed society. Here the “gate” (collapsar jump) is mainly a plot device to enable commentary on time and war, rather than a subject of conflict itself.

- “Dune” (Frank Herbert) – While not gates per se, the Spacing Guild’s foldspace travel functions akin to wormhole creation. The interesting angle is the monopoly: only the Guild navigators (using spice) can enable instant travel, which is why control of the spice = control of all commerce. This resonates with the concept of controlling warp gates in other settings. The Guild ships effectively create a temporary portal that a fleet passes through. The political power derived is absolute, which is a theme a game might emulate by having one faction control gate access.

- Iain M. Banks’ Culture series – The Culture mostly relies on ultrafast starships, but they also have devices called “portal” or “displacement” technology for near-instant travel on smaller scales (for example, in some novels characters step through portals on ships or orbitals to move around). Banks doesn’t focus heavily on galactic gate networks (since Culture ships can themselves tear open wormholes in some stories), but he does present portals as a marker of a highly advanced society where distance is trivial. In one novel (Matter), a portal is used to connect levels of a megastructure, and it malfunctioning becomes a plot point. This exemplifies another use of gates in narrative: as expressions of post-scarcity convenience or as accidents waiting to happen when they fail.

- “Star Trek” Novelverse and Others – The Star Trek TV shows rarely use fixed gates (apart from the Bajoran Wormhole discussed below), but in extended media and some episodes we see things like the Iconian Gateways – ancient doorways that can teleport people across interstellar distances. In the TNG episode “Contagion,” discovery of an Iconian gateway drives the plot, and later Trek novels pick up that thread. Again, an ancient gate, feared and coveted. Even outside of Star Trek, the general trope of a network left by precursors (often with convenient geometric “gate” objects) recurs in countless space-opera tales and RPG settings.

In literature, because authors can delve into characters’ thoughts and long-term societal shifts, warp gates are often portrayed not just as transportation, but as instruments of change and consequence. A gate might enable a galaxy-spanning empire (and the decadence or unity that comes with it), or its collapse might isolate worlds (returning them to barbarism, as seen in stories of lost colonies). The presence of gates can be a way to have a galactic story still maintain close connections between characters (you can get from Planet A to B quickly via gate, so the narrative can jump locations without years of travel – much like a game fast-travel to keep the plot moving). Conversely, their absence or control can generate tension (e.g. a rebel faction seizes a gate, cutting off a core world from reinforcements – a scenario rife in both novels and games). Overall, the treatment of warp gates in novels provides a treasure trove of ideas for gameplay and story: from Hyperion’s cautionary tale of over-reliance on teleportation, to The Expanse’s look at the frontier mentality when new worlds suddenly become reachable, to Hamilton’s vision of a “local bubble” of interconnected planets via wormholes.

Wormholes, Stargates, and Jump Gates in Television and Film

On screen, warp gates and similar phenomena are often used to wow audiences with imaginative visuals, while also serving as plot devices that can kick-start adventures or raise the stakes. Several major franchises have iconic depictions of these constructs:

- Stargate (Film and TV Series): Perhaps the most iconic literal “star gate,” the Stargate is a ring-shaped alien device that creates a stable wormhole between any two gates in the network. In the Stargate SG-1 series (and the original 1994 Stargate film), the gate is a central narrative device: humans discover an ancient ring in Egypt and learn to dial other gates across the galaxy by inputting coordinate symbols. The mechanics in the show’s lore include needing a precise address (7 symbols for within-galaxy, 8 or 9 for intergalactic), a burst of power to establish the wormhole, and a limit of roughly 38 minutes for how long a wormhole can stay open. The wormhole itself is one-way (matter can only travel from the dialing gate to the receiving gate) (stargate.fandom.com), which creates dramatic tension – e.g. teams under attack must get back to the dialing gate to escape; you can’t retreat back through the way you came unless you have the other gate dial back. Visually, the Stargate is brought to life with the shimmering “event horizon” – a pool of rippling blue liquid-like energy that kawooshes outward when the wormhole opens, then settles. This became an iconic TV effect. Narratively, Stargates are portrayed as leftover technology of the Ancients (a precursor race), now used by various species (Goa’uld, humans, etc.). Every episode essentially uses the gate as the portal to that week’s adventure on a new planet, much like how Star Trek uses starships. The show also explores gate limitations and hacks: for example, stargates require an atmosphere on the destination side to establish (so no dialing into space), certain energy fields can block gates, and dialing anomalies can lead to time travel or alternate universes (plot of episodes like “1969” and “Ripple Effect”). Importantly, Stargate made the concept feel grounded by establishing a consistent set of rules (many deriving from plot necessity) and then generally adhering to them. For instance, one rule is you cannot send objects larger than the aperture – leading to suspenseful moments where things barely make it through, or an iris shield on the receiving gate can vaporize incoming travelers by preventing re-materialization. The Stargate franchise, through its longevity, has probably done more to cement the standard image of a sci-fi portal in the public consciousness than any other series. For a game developer, Stargate’s success illustrates how a warp gate can be the core mechanic of a narrative – essentially a door to infinite content – as long as it’s backed by an engaging mythology and constraints that keep stories plausible (even if those constraints are technobabble, consistency is key).

- Babylon 5: This 1990s series has one of the most fleshed-out depictions of a jump gate network in television. In B5, ships achieve FTL by entering hyperspace, a dangerous alternate dimension of swirling red mist. There are two ways to get into hyperspace: large ships can use their own jump engines to tear open a temporary jump point, or smaller ships use fixed Jump Gates that permanently link normal space to hyperspace (babylon5.fandom.com). The jump gates are huge blue rotating structures placed at key points (e.g. near major planets, trade routes, or the Babylon 5 station itself). Narratively, the gate network was built by an unknown ancient race about a thousand years ago and subsequently discovered by younger species.

Races like the Minbari and Centauri found gates in their systems during early space exploration and reverse-engineered the technology to build new ones. There’s a rich economic and political layer: owning a jump gate means you can charge tolls and control access, and thus Earth in its early deep-space age had to rent use of alien gates until it built its own. In wartime, gates become strategic assets – but Babylon 5 establishes an etiquette that destroying a jump gate is a grave war crime since it threatens the entire hyperspace beacon network. Instead, powers will lock out enemies by modulating gate codes (an idea akin to IFF; Earthforce does this against the Minbari during their war). The show also delves into the hazards of hyperspace itself: ships need beacons to navigate from one gate to another, otherwise they can become lost forever in hyperspace’s featureless void. This led to the detail that each jump gate transmits a beacon signal – one omnidirectional (to announce presence) and one directional (paired with a neighboring gate) to guide travelers. If a ship “goes off the beacon,” it risks never finding a way out. This concept was vividly portrayed in an episode where a character’s ship is stranded in hyperspace. From a visual standpoint, Babylon 5 made jump transits memorable: a ship approaching a gate triggers a bright blue “vortex” opening, then cruises down a surreal tunnel of shifting light (the representation of hyperspace) before exiting via another burst. Internally, B5 also had a cool visual for ships with their own jump engines: they’d form an expanding particle sphere and “cut” a hole to hyperspace (appearing as a spiky dimensional rift). All these elements combined to make Babylon 5’s jump gates feel like a complete travel ecosystem – technology with history, rules, and consequences. For game design, B5’s take is inspirational for creating a travel network that isn’t just point-to-point teleportation, but a medium that can be perilous and requires navigation skill. A Wardrome-like game could, for example, incorporate the idea of laying navigation beacons in some “warp space” and have jamming or beacon destruction as tactics. - Star Trek (Deep Space Nine and others): Star Trek typically uses warp drive on starships for FTL, but it has one famous stable wormhole: the Bajoran Wormhole in Deep Space Nine. This wormhole, discovered in DS9’s pilot episode, connects the Alpha Quadrant (near Bajor) to the distant Gamma Quadrant 70,000 light years away (memory-alpha.fandom.com). It is the only known stable wormhole in Trek’s Milky Way, making DS9 station strategically crucial as the “portal” between quadrants. The wormhole’s in-universe specifics: it was artificially created by extra-dimensional beings (the Prophets) who live inside it, and it has a fixed location for each end. Passage is nearly instantaneous – what would normally take decades at maximum warp occurs in mere seconds through the wormhole. The show uses the wormhole for multiple narrative purposes. First, it provides the premise for conflict: its opening leads to first contact with the Dominion in the Gamma Quadrant and eventually the Dominion War (since this invasion route exists). Control of the wormhole becomes a military objective, and DS9 is effectively a gatehouse that changes hands and is fiercely defended. Second, it has spiritual significance: the Bajorans see the wormhole as the Celestial Temple of their Prophets. This introduces a religious dimension to a sci-fi construct, something not often seen elsewhere. The Prophets (wormhole aliens) even intervene at times, notably erasing an invading Dominion fleet within the wormhole in one episode – essentially using their gate as a weapon/protection (much to the astonishment of the characters). Visually, DS9’s wormhole is depicted as a beautiful swirling vortex of blue-white energy that blossoms open and then collapses when traversed. It’s a mix of practical and CGI effects that still stands out as iconic. Star Trek also had other one-off gate examples: e.g. the Barzan Wormhole (featured in TNG) which was nearly stable but had one end drifting, and the Iconian Gateways mentioned earlier (planetary teleportation arches). In the recent show Star Trek: Discovery, a network of ancient wormholes (the “DMA” plot) and a species that lives inside a wormhole-like realm are explored, showing Trek still finds new spins on the concept. For development ideas, Star Trek demonstrates a gate being used as the focal point of a series’ setting – DS9 essentially revolves around a wormhole’s existence – and adding layers of cultural and strategic importance to it. It’s a reminder that a warp gate can be more than just a tunnel: to some it might be a holy shrine, to others a tactical chokepoint, and to others a scientific curiosity.

- Farscape: This TV series follows an astronaut flung to a distant part of the galaxy via a wormhole. Wormholes in Farscape are semi-mystical: they appear unpredictably, and the protagonist Crichton gradually learns to sense and even control them (thanks to alien knowledge implanted in his brain). Throughout the series, wormholes represent the way back home for Crichton – a constant personal stakes element. In later seasons, wormholes become a weaponized plot point: it’s discovered that a wormhole can be artificially stabilized and dropped onto a target to destroy it (essentially a weapon of mass destruction). This culminates in a scenario where Crichton threatens to unleash a wormhole weapon to force peace between warring factions in the miniseries Farscape: The Peacekeeper Wars. Farscape’s depiction is more on the fantastical side; there’s talk of “wormhole technology” that only few have mastered, and visually, the wormhole travel is shown as a psychedelic tunnel (similar in style to Doctor Who’s time vortex or 2001: A Space Odyssey’s stargate sequence). The show’s unique addition to gate lore is tying wormholes to a character’s arc and to big moral questions (would you use a doomsday wormhole to stop a war?). It personalizes the concept – wormholes aren’t common infrastructure here, they’re rare, almost magical routes. For a game, one could imagine incorporating such rare events or abilities that allow instant travel, using them sparingly for major impact, much like Farscape does for big narrative beats.

- Films (Other): Several films have memorable warp gate or wormhole sequences:

- Interstellar (2014): Features a traversable wormhole near Saturn placed by future beings. The depiction of the wormhole as a sphere (a shimmering orb in space that distorts the view behind it) was lauded for its scientific realism and visual novelty – a departure from the typical 2D portal. The transit through the wormhole is shown from inside the ship, with space warping around as they pass through the “throat.” Interstellar uses the wormhole as the premise to reach another galaxy, and later a black hole’s tesseract acts as a kind of one-way warped space for the climax. The film’s realistic approach (consulted by physicist Kip Thorne) could inspire a grounded portrayal of a warp gate in a game, emphasizing how physics might behave near it (time dilation, light distortion) and making the player’s journey through it a unique experience.

- Contact (1997): Based on Carl Sagan’s novel, it features a man-made machine that creates a wormhole transit system. The machine consists of huge spinning rings that, when activated, open a tunnel through space (and possibly time). Jodie Foster’s character experiences a multi-wormhole voyage, depicted in a trippy sequence where her pod drops through a series of portals, seeing celestial wonders in rapid succession. Notably, all that spectacle is completely compressed from the viewpoint of outside observers (they think she went nowhere, as the podrip lasted only a fraction of a second). Contact touches on an interesting idea for gates: frame of reference differences – something that could be an intriguing gameplay or story element (e.g. time passes differently for those who transit vs those who don’t).

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968): The famous “Star Gate” sequence isn’t a technological gate built by people, but rather an advanced alien transportation method triggered by the monolith. When Bowman goes through, the film shows a long, abstract sequence of lights and landscapes – an early cinematic representation of an interstellar wormhole journey, though never called such explicitly. It’s iconic for conveying the beyond comprehension aspect of traversing space-time. While highly conceptual, it seeded the idea in pop culture that a “stargate” could be a pathway to evolution or another plane of existence.

- Marvel Cinematic Universe: Films like Guardians of the Galaxy depict “jump points” – hexagonal patterned portals that ships can use to hop across space (shown in a fun visual sequence where doing 700 jumps in a row causes grotesque stretching of the characters’ faces for comic effect). Doctor Strange and other Marvel entries show magical portals (sling rings) which are more akin to teleportation circles. While more fantasy than sci-fi, they demonstrate the widespread appeal of portals as a visual and plot device (often allowing quick travel or surprise appearances in battle).

- Stargate (1994 film): We discussed Stargate in the TV context, but the original film deserves a note for how it introduced the concept to a wide audience: the awe of stepping through an alien portal to another world (a distant planet with ancient Egyptian-like culture). The film’s dramatic buildup – dialing the gate symbol by symbol, the wormhole kawoosh, then the harrowing first transit – effectively sold the idea that such technology is both thrilling and frightening. Games often replicate that same sense of buildup when using gates (charging up animations, or requiring multiple steps to initialize a jump, as a way to create anticipation).

Across TV and film, we see recurring design patterns similar to games and novels: warp gates are frequently ancient artifacts (Stargate’s Ancients, B5’s Gatebuilders, Iconians in Trek), they often require specific keys or codes (Stargate addresses, B5 access codes, Halo’s Portal activation by keyship) to operate which provides narrative control, and they can be sources of conflict (who controls the gate) or salvation/destruction (wormholes to escape a threat or to unleash one). Visually, almost every portrayal emphasizes spectacle – swirling energy, dramatic lightshows, objects stretching or blinking out. This makes sense: a gate sequence is a chance to astonish the audience. In an interactive medium, it’s likewise an opportunity to wow the player with a sense of crossing a threshold.

Common Themes and Design Patterns

Across all these franchises and mediums, warp gates share several common themes and design elements:

- Ancient Origin & Precursor Networks: A striking number of settings attribute gate technology to long-dead civilizations. This holds true in Mass Effect (Relays by the Reapers), Babylon 5 (built 5000+ years ago by unknown aliens), X Series (the Ancients), Stargate (the Ancients/Lanteans), Homeworld (the Progenitors), and many novels (Hyperion’s farcasters given by AIs, Seven Suns’ Klikiss transportals, Iconian gateways in Trek, etc.). This pattern serves two purposes. First, it adds mystique – the gates are “magical” beyond current human science, allowing the writer to include them without over-explaining, and giving characters a sense of wonder or respect. Second, it provides plot fuel: the creators’ intentions can be a mystery or a threat (e.g. Reapers using the relay network to manipulate civilizations). For a game like Wardrome, deciding who built the gates can significantly shape the lore – are the players using dimly understood relics (implying perhaps some could malfunction or have unknown features), or are these gates a recent invention of the current races (implying a certain level of contemporary engineering mastery and perhaps more control over their operation)?

- Choke Points and Strategic Value: Almost universally, warp gates concentrate travel along certain routes. This inherently creates choke points and hubs, which stories and games leverage for drama. In EVE Online, star systems with many gate connections (hubs) become bustling trade centers – and also targets for blockades. In Babylon 5, possession of the only route to the Gamma Quadrant (the wormhole) makes DS9 and Bajor incredibly strategic.

In The Expanse, Medina Station (formerly the Behemoth) set up shop inside the Ring hub to control traffic between all 1300 worlds, literally turning a generation ship into a customs checkpoint for a galaxy. Strategically, this is gold: it’s the Panama Canal of space. For game design, this pattern suggests that implementing warp gates can naturally introduce conflict zones: expect battles at gateways, expect factions to fortify or toll them, expect gameplay centered around either securing a gate or sneaking around via alternate routes. It can also justify asymmetrical warfare – a smaller force can hold a gate against a big fleet if the gate is the only entry (like Thermopylae in space). Map design in RTS or 4X games often explicitly reflects this, with “nodes” connected by limited links. Even in open-world games, developers might simulate this by having only certain hyperspace entry points or jump algorithms that force predictable endpoints. The theme of gates as strategic assets is one Wardrome could embrace, perhaps by making some star systems gate-rich crossroads and others isolated backwaters – giving players reasons to fight over, say, a central warp nexus that grants quick reinforcement across the sector. - Maintenance, Power, and Limitations: Warp gates often come with technical caveats. They might need enormous energy to operate, or rare materials to build (Quantium-40 in B5 is vital for jumpgate construction, hence extremely valuable). Some gates only connect to one fixed partner (Mass Effect’s primary relays are paired; Babylon 5’s gates have set beacon links), while others form a mesh network. There are also often safety protocols or limitations: e.g. maximum wormhole duration (Stargate’s 38 minutes), mass limits (Stargate can’t send high mass continuously, Babylon 5 enlarging a jump point needs exponentially more power for bigger ships), or cool-down times. In gameplay, these translate to interesting mechanics: one could have a gate that only opens periodically (creating a window of opportunity theme), or requires charging up (so players must defend a generator until it’s ready). The need for a rare fuel or component can drive mission objectives (e.g. collect exotic particles to fire up an dormant gate). On the flip side, if gates are very reliable and free, that implies a post-scarcity ease of travel which might diminish traditional logistical gameplay – so many games counteract that by introducing a cost or constraint. EVE Online’s limitation on capitals not using gates, for example, ensures there’s still a use for jump drives and that huge ships can’t invade high-security space easily. It’s a balancing lever. Similarly, in strategy games like Stellaris, gateways are a late-game feature and often require heavy investment to activate or build (plus tech research), so the early and mid game still hinge on slower travel, which provides a paced progression. The drama of power usage is also a theme: we see in Halo that overpowering the slipspace portal or misusing it can risk damage, and in DS9, we see technobabble about neutrino levels spiking right before the wormhole opens – little touches that emphasize that these are powerful, almost volatile devices.

- Societal Impact – “Distance is Dead”: When gates are abundant and accessible, stories often explore how they shrink distances and what that does to societies. With farcasters or wormholes, a galactic empire can function almost like a single city. Trade, tourism, even warfare become faster (imagine blitzkrieg through a gate network). Many utopian or high-tech civilizations in sci-fi have such gate networks underpinning their economies – it’s essentially a sci-fi version of the internet (instantaneous connectivity) but for moving physically. However, the flip side is also explored: if that network fails, you get collapse or fragmentation (as in Hyperion or any “Fallen Empire” setting where once there was a gate network and now worlds are isolated). This contrast is a recurring plot in games and novels, often referred to as the “Sundering” or “Fall of the Jump Gates” etc. For Wardrome’s development, one might consider whether the game world is in a Golden Age of gate travel (lots of connectivity, implying a more cosmopolitan and densely interactive map), or in a Dark Age after gates fell (implying more isolated pockets, unique regional developments, and a quest element of re-linking the network). Both scenarios are rich with storytelling potential. Also, the social stratification that can result is interesting: who gets access to gates? In some stories, like Hamilton’s Commonwealth, everyone uses them freely (public infrastructure), whereas in others, like some Star Wars Legends tales, maybe only certain elite or military have gate keys. If a game wanted to incorporate that, it could tie into player progression (e.g. you need to earn trust or resources to use certain gate routes).

- Visual and Thematic Consistency: From a design perspective, warp gates benefit from having a strong visual identity – think of the Mass Relay silhouette or the Stargate ring and how instantly recognizable they are. Nearly every franchise gives their gates a distinctive look and feel (even within the same trope of “big ring,” the execution differs: Stargates are engraved stone-like devices with chevrons, Babylon 5’s gates are metallic rotating tori, No Man’s Sky’s portals are monolithic slabs with glyphs). Consistency in how gates are portrayed (the effects when they activate, the sounds, etc.) helps suspend disbelief and builds audience/player intuition. For example, viewers learn that a blue puddle means an active wormhole; players learn that a certain glow or UI icon means a gate is available to use. On a thematic level, many gates are surrounded by a bit of ritual or procedure – SG-1 always shows the “dialing sequence,” B5 often shows the captain asking for jump clearance or a vortex opening sequence, games like Freelancer actually require the player to request to dock with a gate or trade lane. These small procedures make the act of using a gate feel like a part of the world (with air traffic control, protocols) rather than just a gamey teleport. They also create moments of tension or relief (escaping just in time through a gate, etc.). In writing or designing Wardrome, focusing on these presentational details could elevate warp gates from a mere mechanic to an experience for the player. Perhaps the game could have a dramatic animation and sound when a fleet jumps in via a gate, or an entire mini-game of tuning coordinates for a long-distance jump.

- Perils and Unknowns: While warp gates enable adventure, they are also often sources of danger or at least uncertainty. The phrase “Nobody knows what’s on the other side” is a classic – be it stepping through a stargate to a new planet (could be hostile), or opening a wormhole (could bring back something unexpected). Sci-fi frequently uses gates to introduce the other, the alien. In Stargate Atlantis, the expedition goes through a gate to an entirely different galaxy and finds a new nemesis (the Wraith). In The Expanse, going through the rings awakens ancient killing machines between galaxies. In Half-Life (a game example), opening a portal to another dimension literally starts an alien invasion. Thus, warp gates often carry a narrative warning: doors swing both ways. If you can quickly go out, something can quickly come in. That notion provides built-in stakes for maintaining defenses and vigilance around gates. It’s not surprising many settings have gate monitoring stations, locks, or even episodes about “what if something bad comes through” (the very first Stargate SG-1 episode after the film is about an alien coming through the Earth gate unexpectedly). For Wardrome’s context, this could inspire events like surprise incursions via gate, or the need to recon a destination before sending the main force. It also justifies things like gating technology behind certain narrative progress (no one wants to open a portal to literal hell in turn 1!).

In conclusion, warp gates in sci-fi serve as both enablers and equalizers: they enable grand scales of exploration and empire, but also equalize by nullifying the advantages of distance. They introduce strategic and narrative challenges that repeat from game to book to film – control, access, technology, and the unknown. By studying how various franchises implement these gates, we can extract ideas for Wardrome’s design. For example, Wardrome might implement a gate network for fast travel but include some of the limitations seen in other works (perhaps each use has a cooldown or requires a particular resource, making timing and control key). It could integrate lore – maybe the gates in Wardrome were left by an old civilization and part of the game is discovering lost gate nodes or reactivating them (adding an exploration element similar to finding derelict relays or jump points). The game’s art and audio could take inspiration too – a signature portal effect that players come to associate with strategic opportunities or dangers.

Ultimately, warp gates capture the imagination because they represent mankind’s triumph over the vastness of space – a tantalizing shortcut in a genre usually defined by light-year distances. Whether in a video game map or a space-opera epic, they provide a framework that brings far-flung worlds within reach and focuses conflict and cooperation into key points. This excursus through their depictions shows a rich lineage of ideas to draw from, ensuring that warp gates in Wardrome could be implemented in a way that is not only functional for gameplay but also resonant with the grand tradition of science fiction storytelling.

Design decisions in Wardrome

The gateways.

In Wardrome, every sector of space is connected by eight automatic wormhole gates, forming a vast lattice across the known universe. Each gate links to the adjacent sectors, allowing seamless travel for fleets without resource cost or cooldown.

When a fleet passes through, it doesn’t emerge at a fixed point — instead, it arrives in an unpredictable zone of the destination sector. This randomness preserves a sense of tension and discovery even in familiar regions.

For now, gates simply serve as instant conduits between neighboring sectors. But in the future, we plan to introduce adventures within the wormhole tunnels — encounters, phenomena, and lost travelers drifting between realities. Other types of special gates, with unique behaviors or destinations, are also on the roadmap.

We deliberately chose this simple initial implementation to keep navigation smooth and fast, while leaving every narrative door wide open for future updates.

Lore Integration

Wormhole gates, once created by the ancient SEATOGU enterprise, leaders of the Technocracy, enabled near-instant space travel — a revolution that reshaped exploration, commerce, and warfare alike.

As centuries passed, the knowledge to maintain these gates faded, and the network fell into disrepair. Humanity regressed to slow propulsion, its star lanes growing dark.

Refusing to accept this decline, a small group of scientists and engineers worked tirelessly to recover SEATOGU’s lost technology. Their success rekindled the spark of interstellar travel, restoring the gates and reigniting humanity’s reach across the stars.

Yet, the network now connects the universe only step by step — sector by sector — making true galactic exploration almost impossible. Beyond each restored gateway, the unknown still waits.